Synopsis

The change of seasons is such a self-evident phenomenon that we take it for granted yet we struggle to catch it in the act. Look outside - the nature seems so static compared to the hectic lives we must live. At best we might notice a sudden heatwave or an unexpected freeze, a violent storm or a particularly vibrant sunset. But in fact nature is everything but still – it’s in constant motion changing and morphing, we just function on different timescales. Maybe that’s the reason we sometimes struggle to grasp bigger shifts such as climate change?

The obsession with trying to bring those timescales closer for me started with time-lapses where with relatively simple techniques I could speed up hours and translate them to human-perceptible seconds. I was fascinated by the results, but soon after found myself wondering - what’s next? At the dawn of drone photography I briefly played around with aerial time-lapses, but the results were somewhat lacking. That is until the spring 2019 when I asked a simple question - what if I could somehow speed up the change of seasons and at the same time showcase the nuanced beauty of Latvia which just happens to be blessed by proper four seasons? And do it in the most dynamic way possible to pay homage to the fluid nature of the nature (what a mouthful!).

About 30 locations all around Latvia where chosen - from the iconic bends of river Daugava and the lake district of Latgale to the ancient valley of Gauja National park to bogs of Ķemeri National park, the rocky beaches and rolling hills of Vidzeme, pine forests of Kurzeme and agricultural lands of Zemgale. Unsure how much of it would end up in the final piece (in fact - more than a half of material didn’t make the cut), I kept driving thousands of kilometers, returning to the same locations over and over again. Amidst all the logistics and technicalities thoughts about the meaning of it all kept creeping in. The value and fragility of present, the coming of better times and the passing of bad ones, the inevitable cyclicity of it all yet at the same time the uniqueness of each cycle. In this case nature being a mere catalyst for the philosophy behind it.

At first there was an urge to create a conventional story, but the more I tried to build a narrative the more I felt no need for it. There was no clear beginning or an end to this story as it is with the nature itself. I ended up choosing an arbitrary length for the video fully realizing that some viewers could exit at any point (based on statistics of any video - most do just that) and some could be left with wanting more or using the video as pure background piece.

While researching the nature of change the texts of French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) and his process philosophy resonated deeply with what I was trying to convey using my moving images so much so that I included a couple of his quotes in the video. To expand on that would mean a long and uneasy read, but here’s an excerpt from Henri Bergson’s series of lectures “The Perception of Change” (“La perception du changement”) which introduces his school of thought and is also applicable to the context of this project:

Change is absolute and radical: it has no support. We are misled by sight, which is only the avant-garde for touch: it prepares us for action. But if we switch to hearing a melody, we have a better sense of indivisible change, although we still do have a tendency to hear a series of notes. This is due either to our thinking of the discontinuous series of efforts needed to sing the melody, or because we see the notes on the conductor’s script. But if we come back to sight and think about what science teaches us, we see how matter is dissolved into action, how there are no things that move, but only changes in the rhythms of motion. Nowhere do we see this “substantiality of change” better than in our inner life. We are misled by thinking of a series of invariable states with an unchanging ego for support, like actors passing over a stage. But there is no underlying thing-ego that changes. All we are is a melody; this is our duration (interfused heterogeneous continuous change), although we are led by practical interest to spatialize this time.

Technical

From a simple idea to lengthy execution

The Ground Work

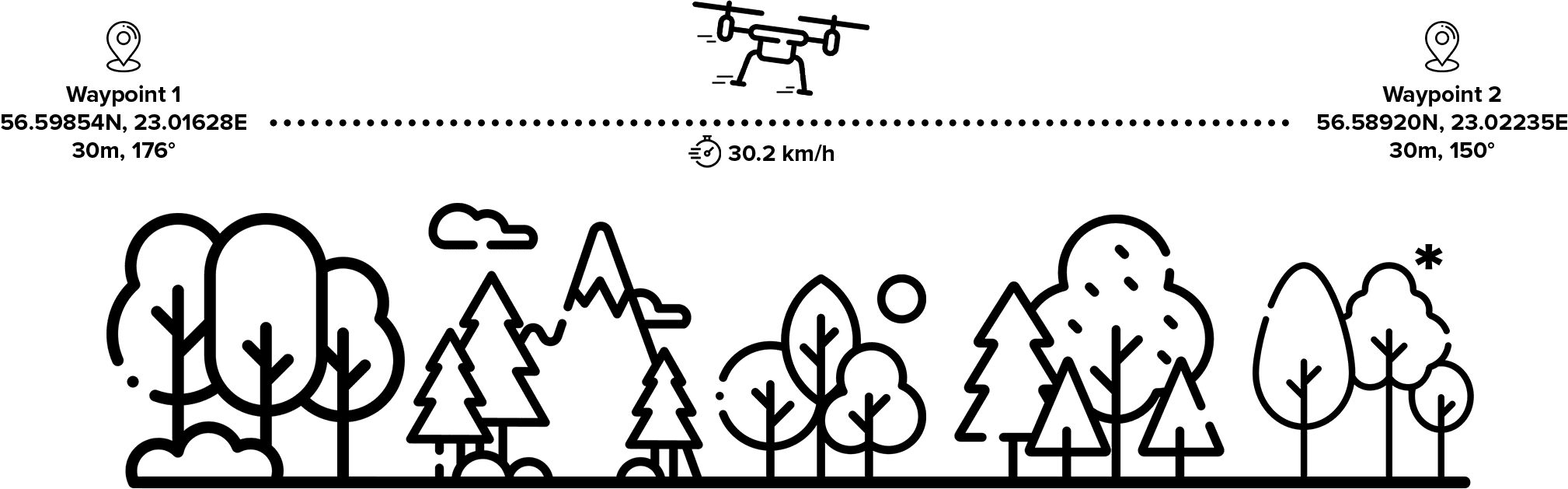

The project was filmed using a DJI Mavic 2 Pro drone controlled by a third-party app called Litchi. The idea was simple: arrive at a location (or more often than not camp there), launch the drone, compose a shot, record the starting GPS location, height and heading, fly to the final location, record the same values in addition to the desired speed and what video mode was used (HQ or full FOV), save it all as a mission to repeat next time, lay back and let the robots do their work. And this is where simple part ends.

*Icons made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com

The Production

Mission setup in Litchi. 1 of 124.

The first round of flights (spring season) where just like any other - compose a shot that looks good and fly away. To maximize the coverage of a location I would do several flight paths in all directions (on average - 4 per location) which did mean working with the Sun as to avoid shooting straight into it and in general avoid unfavourable lighting conditions. Come next season I was greeted with a self-evident revelation that we live on this space rock that circles its star, but addition to that it revolves around itself hence the Sun travels around the sky and at the same time of the day lands in different locations each season. This meant that all the careful compositing of the first season was out of the window and only in circumstances of pure luck was I able to get a decent shot. And, mind you, there were two more seasons to go. I must admit, this was a bit frustrating as most of the times the light was good (I planned drives around it), but it was just in the wrong direction which was useless for my case. But I kept chugging along, hoping for the wonders of post-production.

The Issue

After thousands of kilometers driven, liters of coffee consumed and gigabytes of data gathered it was time to put it all together, layer the shots on top of each other and call it a day. And this is when it struck me – the shots did match AT ALL.

Let me explain.

One waypoint, four diffetent perspectives

You see, I was using a consumer drone which has a consumer GPS with an accuracy of 2-5 meters. This wouldn’t be much of a problem for high altitude shots since a meter here or there wouldn’t change much in terms of the perspective. But the closer you get to the ground the more severe the shifts in perspective become apparent. Just look at your screen, then move 1 meter to the right by keeping the screen stationary. A completely different scene is what you get.

Oh, and did I mention the fact that GPS is two-dimensional? Meaning it only records the longitude and latitude. What about height? Well, height in consumer drones is measured using barometer. In other words - it’s measuring the air pressure. And - to no surprise - it’s not a constant. To add to this – the recorded height of a waypoint is relative to the take-off point of the drone, not absolute relative to the sea level. So launch the drone a bit higher or lower and you’ve got yourself yet another offset.

To recap - I had to deal with 3-dimensional shifts of perspective which got more exaggerated the closer I was to the ground. This is not something that can be fixed by 2-dimensional repositioning and aligning of shots. More about that in the post-production section.

Nine states of the same landscape.

As if this wasn’t enough - there were two more variables. One was the speed. The mission had a pre-programmed speed value, but it was impossible for the drone to follow it precisely due to the random nature of the weather. A short wind gust would throw the whole timing off. The second variable had also something to do with the wind - the position of the gimbal (and thereof the framing of the shot) was recorded relative to the drone. Let’s say - keep a 15 degree tilt down. But due to the wind the drone had to compensate by leaning into it at various angles. As you can see from still frames up above this meant that the horizon was off on each and every shot. Which in turn meant that while aligning shots a lot of information (either in the sky or on the ground) would be lost. Hence the wide aspect ratio of the final video that crops off lost pieces.

Simulated flight of four identical missions highlighting differences in altitude, speed and attitude.

The Post-Production

The first task was to align all raw material. This meant going through about 500 takes (124 locations, each 4 shots on average) and finding the beginning of each take. In other words - the timecode in the raw file where the drone was exactly on the 1st waypoint. This was never the beginning of the file. This fairly straightforward task proved to a bit of a challenge, because paired with the inconsistencies of framing and perspective a lot of guesswork and juggling was involved. See a sample of four raw takes below. Notice the differences in length, framing, speed and miniature inconsistencies of the later (probably caused by wind):

Due to the obvious variability of all factors it was clear that doing 100% 1:1 match between all takes in their full length would be impossible, therefore I focused only on points of contact, that is - only where two pieces of footage meet at one time and only for the duration of the desired transition. But to sell the effect, both footages must match perfectly during the transition. The answer was warping - pushing and pulling of a virtual blanket in order to match up features in the shot. And then animate the warp to match the movement. Of course, because of the nature of parallax, pure warping would not solve the issue of relative positioning of features - if a tree is visible in one shot, but hidden by another tree in another shot just because the drone was lower, then there was nothing I could do about it. Instead I chose to focus on matching the foreground elements with the hope that inconsistencies further away would escape the eye.

Here’s a sample of one complete take:

A here’s one shot’s warping singled out:

Warping was done in After Effects using various blending modes to see through layers. Blessed where the shots with man-made structures since clear geometrical shapes were much easier to match than say tree trunks and branches which not only are hard to make out (leafless winter vs. full bloom summer), they tend to move and… trees actually grow a bit during one year!

All this warping and cropping meant only one thing - lost resolution. 4K final material is the standard these days, but in this case not much of the source 4K was left and this would have been a great use case of larger resolutions - 6K or even 8K. Wanting to still deliver in 4K, I turned to AI for help. Namely used Topaz Video Enhance AI software which by using some sort of witchcraft is able to recover (or should I say - recreate) lost detail and bring back life to otherwise mushy material.

To sell the effect of seasons changing various transition methods were considered - from simple fading to masking. It was decided to go with a gradient wipe transition since offers a gradual translation instead of a global. Using the same footage layers as gradient maps and interesting effect emerged, for example - when transitioning from autumn to winter and using the greyscale winter as a map (white fields, black trees) open fields would fade in first and trees later. Just like in nature where the first snow lands on flat areas and only then covers vertical trees. Same effect in transition to spring, only reversed - snow disappears from trees first and from fields last.

The final step was color which also required a different approach than usual. A completed transition shot would consist of four or sometimes even more different shots with different colors, contrast and lighting. Using the same grade on all would lead to a mess. Usually color grading comes as a last step, but in this case each of the individual shots had to be prepared in advance i.e. before the transition. The grade was simple - noise reduction, exposure correction, converting from log to rec709 and then some local adjustments for the sky and the ground with a little color push at the end (mostly bringing out some vibrance in autumn or correcting greens in different summer lighting scenarios). The transitions would then get rendered by backing in these grades in. This was done for all 124 scenes, because it was unknown what will make the final cut.

The second and final layer of grading would happen at the very end of editing and only on used material. As this was not a stylistic movie, the choice was to avoid extreme color shifts in the name of style. We’re talking nature here, after all. So no film emulations, LUTs or anything like that. Only subtle adjustments to exposures and colors, sharpening, grain and glow. Some of the adjustments still needed to be animated in cases of extreme changes in seasons.

Media

And that’s it, that’s the project wrapped.

Hope you enjoyed it and thank you for making it to the end!